ANTHEM’S LONG STRANGE TRIP

ANTHEM’S LONG STRANGE TRIP

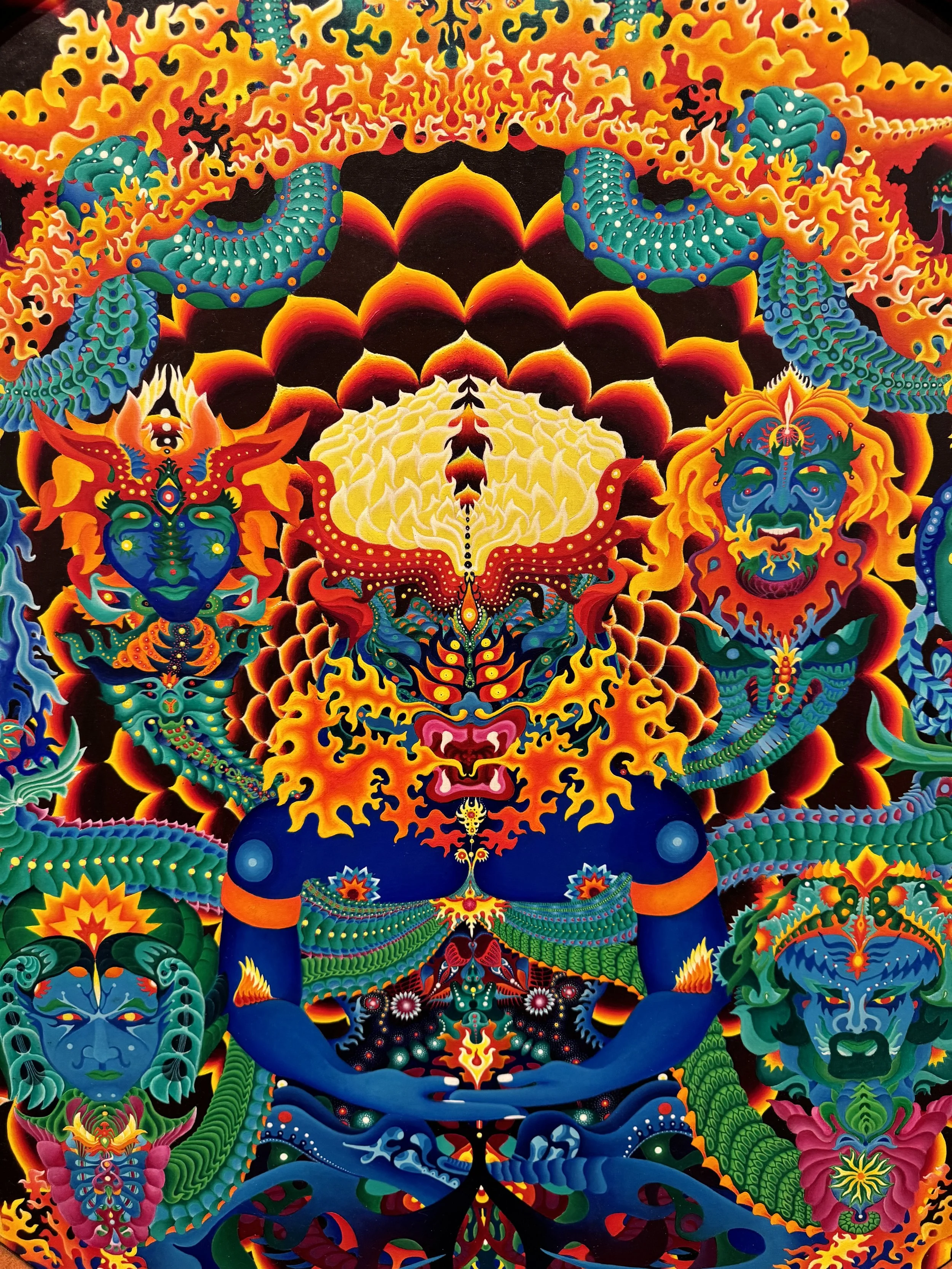

This is a short(-ish) version of the story behind the painting, used for the Grateful Dead’s second album in 1978. The painting was unfinished at the time, and this chronology follows it to the present day.

It’s a short read, but you might want to get comfortable, and turn on some music while you do. Here’s a suggestion.

It began with the stars. At a four years old, in 1942, I remember gazing up at the Arizona night sky, trying to count all the stars, only to give up when I realized the sheer enormity of it all. This early moment ignited a lifelong fascination with the infinite, with the interconnectedness of all things. The interplay between the infinitely large and the infinitesimally small fascinated me, and those early encounters have been the fuel of a life-long curiosity and expression.

Because I wore thick glasses from age five I wasn’t into contact sports. Instead I had a pencil in hand, drawing constantly: war machines that I saw on the news reels: horses, animals, and eventually portraits. I had no art education as a kid, except for a drafting class in high school. Instead, my life revolved around horses. My mom broke the quarter horses of the moneyed snowbirds from the east who came to Tuscan, AZ. Besides having a lot of responsibility at a young age and shoveling a mountain of horse shit, breaking in those horses was dangerous as hell, and I learned how to read every twitch, every possible signal as to their state of mind. If there’s anything I learned to do well and early, it was to pay attention to minute details.

I grew up in a turbulent world. WWII, the Bomb, Sputnik. As a teen, we lived in Las Vegas. One morning with my brother and some friends, we mounted a ridge 120 miles away from the Nevada Test Site. Awesome it was! Out of a silent, cold darkness in an instant! It was as bright as day for perhaps five seconds, after which the light seemed to contract into an intense reddish orange fireball which faded into a ghostly dull reddish gray rising column. Then came the sound of the blast, the shock, heat, and ground waves which were felt in every cell in my body". Later I understood it as the dual potential for creation and destruction inherent in scientific advancement, a tension between chaos and order. This tension found its way into Anthem, where chaotic elements intertwine with moments of harmony, reflecting the balance I saw in both the universe and within myself.

… Wait, this is the SHORT version?…

Yep, keep going! Or checkout this 12 minute documentary with Bill and art historian, Dr. Michael Pearce.

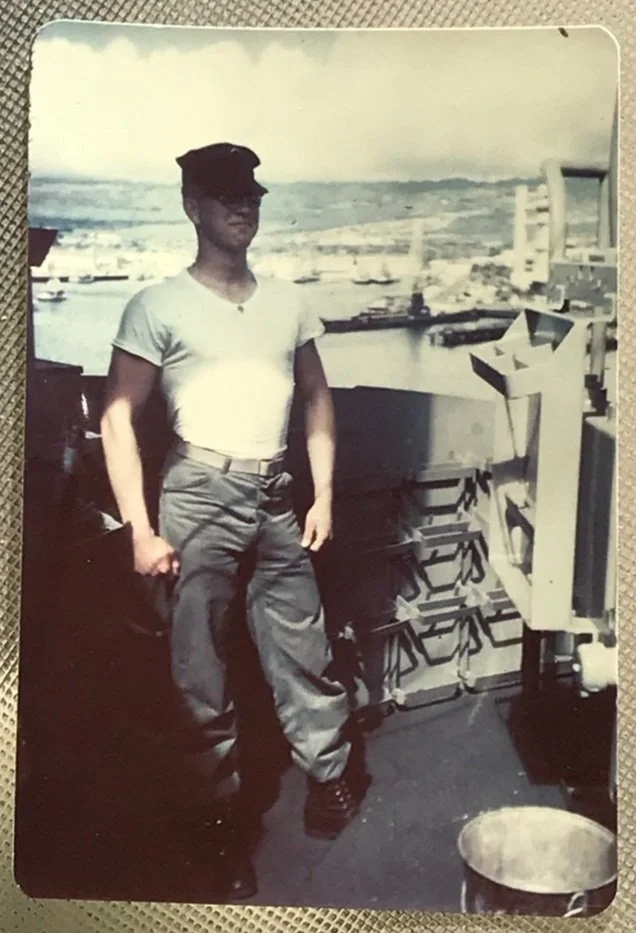

After high school (1956), I enlisted, as service was mandatory or risk a draft. I chose the marines because they traveled abroad. Traveling aboard ships across the Pacific, from Hawaii to Japan and the Philippines, I found myself captivated by the Asian cultures I saw where art permeated everything. As a captain's orderly, I was body-guard and chauffeur when we were in port, and we spent a lot of time in Japan. Life was good at the base of Mt. Fuji, hanging out in hot springs, and reveling in Japanese hospitality. Simple things blew my mind.

It was the Kamakura Buddha, a 40ft bronze statue, which was my first glimpse into Buddhism. Then later on leave in 1958, I traveled to Nepal. It was the time when China was invading Tibet and refugees were flooding Kathmandu. On arrival, I promptly got dysentery - which made me a great fan of antibiotics, cause that shit is no fun - but crushed my hopes of making it to base camp at Everest. What stuck with me was an encounter with a Buddhist nun, wearing a wrap of human finger- and toe-bones, drilled and woven as a mesh over her skirt. Her presence was immense, and I later understood the garb was a recognition of status and spiritual achievement. Add her to the yogis and esthetics, and I had brain food for a lifetime.

My tour in the Marine Corps ended in 1960. I didn’t know what I wanted to do and was thoroughly traumatized by the Corps. The transition back to unstructured civilian life was hard. That said: I knew I needed to go to university. I enrolled at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. In a short while, I found that the poets and artists were having more fun than the scientists, and one drawing class led to another, and I decided to study art.

Bill Walker, Marine corps, circa 1958.

鎌倉大仏, Kamakura Daibutsu - Wikimedia Commons

It was at UNLV that I made some of the most meaningful connections of my early life, particularly Phil Lesh, the future legendary bassist of The Grateful Dead, and Tom Constanten (“TC” as we called him), one of their inspired keyboardists and composers. Our shared passion for music, whether it was classical compositions or avant-garde experimentation, became a huge influence on my art. I envied their brilliance in music, and wanted to find the same brilliance in my own art.

Phil was a true inspiration and he moved to a spare bedroom in my house in Las Vegas. I was in awe of his musical abilities, his avant-garde approach, calling him a "wunderkind" with perfect pitch and a mind that could recall anything. While living with us, he was composing his piece called Foci, an orchestral work that radically pushed the boundaries of conventional music. Our house was filled with music, philosophical discussions, and a variety of (occasional) mind-expanding substance, all of which contributed to a shift in my broader consciousness and artistic style.

It was in this environment that my consciousness began to notably shift. I was constantly inspired by the way Phil could break traditional musical boundaries, just as I was pushing my art to. My growing interest in Eastern spirituality starting with the book Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, lit up my reflective being.

UNLV art class project. Bill Walker, circa 1963.

Expanding Consciousness

I was first introduced to peyote through a friend of my uncle, “Jim Shit”, a road-man in the Native American Church. Jim explained, “Most people today don’t have a very close connection with their real self and the real world and peyote can resurrect that connection.” I was familiar with the concept of self-realization through yogic teachings, but I wanted to know what he meant by “real self.” He answered:

“You see, you were not born Bill Walker, that’s just the name of the personality you have developed to get what you want and avoid what you don’t want in the world of people. Who were you on the first day you were born?”

And, at the time, there was something missing in the way I had been living, something that felt disconnected from the essence of who I was. There was a deep urge to reconnect with my "real self," to understand what it truly meant to "live right."

And as luck would have it, a friend of mine arrived with a large number of peyote buttons (the trunk of a Chevrolet Corvair full of it). For the next year, I and my friends in the Mobius Band (more friends from UNLV) ate the dried peyote every few weeks, often in the natural landscapes around Lake Mead, the Valley of Fire, and Red Rock Canyon.

At first, the experiences were overwhelming, even frightening, but they eventually opened up a new way of seeing—where music, colors, and forms seemed to merge, revealing an inner dimension to reality. In fact, I began to perceive music as color, and form as sound— “synesthesia”, as it is called — blurred the lines between senses, creating a sense of interconnectedness that I hadn’t known before, and I could achieve a state of clarity and harmony.

As I became more experienced, I found they weren’t just about seeking visions or insights; they were about learning to control and stabilize my mind as I ventured deeper.

Exploring Inward

Besides tripping around the desert in Las Vegas, I also bounced between San Francisco and Hawaii during the mid-1960s. My time in San Francisco was pivotal, coinciding with the city’s emergence as the epicenter of the counterculture movement. It was an incredible time of artistic and musical experimentation, and Phil, TC, and I were there for the ride.

In 1963, the three of us shared a house in the Mission District. This was before the Summer of Love and the full explosion of the psychedelic scene, but the seeds of that cultural shift were already being sown. For us, it was a time of intellectual exploration and deep engagement with music. Phil was already deep into his own musical journey. We spent hours in deep listening sessions, immersing ourselves in everything from classical composers like Beethoven and Brahms to avant-garde works by Berio, Ligeti, and Varèse. These sessions were more than just about enjoying music—they were about breaking it down, understanding its structure, and exploring how sound could transcend traditional forms.

TC had recently returned from Europe with new ideas and compositions that expanded my understanding of what music could be. He was a composer unlike any I had ever known, someone I still think of as the "quintessential Zen composer." His music was like a series of Zen koans—challenging, sometimes perplexing, but always rich with meaning if you were willing to engage deeply with it. TC’s approach to music forced me to rethink my own ideas about creation, and his avant-garde sensibilities opened my eyes to new artistic possibilities.

During those times in SF, I spent a lot of time drawing, often setting up on the sidewalk or in Golden Gate Park. I would sell my drawings for a few dollars or just enough to get something to eat.

I felt deeply connected to the energy of the city, but by early 1964, I started to feel a pull back to the desert. I needed to reconnect with the dirt and the sky, the wide-open spaces that had always inspired me. San Francisco had fed my mind and expanded my artistic horizons, but the desert called me back to something more elemental, something that felt like home.

New Year’s Eve at Rogers Springs, NV, 1964-65 was among the most transformative experiences of my life, a night that fundamentally shifted how I understood myself and the world. I had been seeking something deeper for a long time, and I knew that this peyote journey would be a turning point. But I wasn’t prepared for just how profound it would be.

I chose Rogers Springs for a reason. It’s this beautiful, isolated natural hot spring about 50 miles north of Las Vegas, a place that felt ancient and alive, where I could really connect with the land and prepare myself for what was to come. I took the whole day to get ready—ran to the Valley of Fire and back, gathering firewood, cleansing myself in the hot spring, and setting up a small fire as the sun began to set. It felt like a ritual, a way to ground myself before diving into the unknown. I climbed into this small cave that overlooked the springs, and that’s where I sat down to prepare the peyote. I busied myself with tending the fire and contemplating what an awesome circumstance this was. I was a very fortunate human being to be in this primeval place and have the opportunity to take part in this most profound rite of communion, that people of this land had performed ceremoniously for thousands of years

After eating twelve peyote buttons, the experience hit hard and fast. The purging came first—violent, but somehow cleansing. After that, the visions started. I began to chant, tapping a stick on my peyote bowl, trying to focus my mind and enter the experience fully. That’s when the peyote really took hold. I was suddenly aware of a coyote standing nearby, watching me. In Native American tradition, the coyote is often seen as a trickster or guide to the spirit world. But instead of honoring it with an offering, I hesitated. That moment stuck with me—my failure to acknowledge the coyote’s presence disrupted my flow. I felt uneasy, chilled, like I had missed something important.

The visions became more intense. I found myself inside this swirling vortex, the "Rainbow Serpent." It was powerful—alive, transformative. I could feel this energy coursing through me, pulling me deeper. But before I could fully surrender to it, I was shaken awake by my friend Jim. In my altered state, I perceived him as Mescalito—the spirit of peyote. He offered me a cigarette, a small but profound gesture that broke me out of my usual habits and forced me to let go. It was as if Mescalito was telling me that I had to surrender to the experience completely, to stop trying to control it. He said, “That’s the Rainbow Serpent and you shouldn’t fuck with her. You don’t have enough inner strength or control. She is the very essence of life within you and the world.”

Things took a strange turn after that. Jim transformed into Two Crow—a pair of identical, mirrored crows that began mocking me for my earlier outburst. They were playful but sharp, like spiritual tricksters. The duality of these two crows reminded me of the opposing forces within me, the contradictions I hadn’t fully reconciled. TC used to talk about "parallel nowheres," a concept from quantum theory, and in that moment, I understood it viscerally. It wasn’t a theory—it was happening right in front of me. Two Crow was a reflection of the many layers of reality, the dualities within myself and the universe.

Jim, or Two Crow, eating datura seeds - by Bill Walker

Back to Dirt & Water

By the time the visions faded, I was drained—physically, emotionally, spiritually—but also clear in a way I hadn’t been before. I saw the truth that I had been avoiding: I wasn’t living authentically. City life had pulled me away from what mattered, from my connection to nature, to the dirt and the sky. I knew I needed to change, to live more in tune with what I had experienced that night. In the following two weeks, I either sold or gave away everything except a tee shirt, levis and a pair of sandals. Then I bought a ticket and flew to Hawaii.

On Oahu, I hitchhiked to a remote beach on the west side, a place where I could just be—no distractions, no obligations, just me and the beach. For two months, I lived on that beach, completely immersed in the rhythms of nature. There was something about the Hawaiian landscape that slowed everything down for me—time, my thoughts, even my body. I let the sun and the ocean dictate my days, and I learned to live simply, living on fresh coconuts, papayas, and Kiawe beans, harvested from trees lining the beach. This was what I needed. It allowed me to find a sense of peace and equilibrium, to process the intensity of the visions and encounters I’d had.

Eventually, though, I needed to earn some money, so after my two months on the beach, I made my way to Honolulu. I found work in construction, building rock walls, which helped me get by. I spent my free time at Ala Moana Beach Park, living out of my Volkswagen van, swimming in the ocean and watching the sailboats in the harbor.

This growing interest in sailing led me to join the crew of the Carthaginian, a 137-foot barkentine that had been used in the filming of the movie Hawaii. For several months, we sailed through the Hawaiian islands, and sailing brought me closer to the elements, and that connection would later find its way into my artwork.

During my time in Hawaii, I also began to sketch again. One drawing in particular felt like a culmination of everything I had been through over the previous two years. I’ve since finished to my liking. Not a little bit inspired by The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel an epic poem by Nikos Kazantzakis (Phil turned me to that one).

My Odyssey - Bill Walker, mixed media and digital

The Genesis of The Grateful Dead

While in Hawaii, Phil and I continued to communicate via postcards. One day, I received a postcard from Phil that read:

"GREETINGS TO THE AMBASSADOR PLENTIPOTENTIARY FROM THE LAND OF ZONK! ALL THE BEST FOR THE HOLY DAYS!!! I'VE SIGNED ABOARD A PSYCHEDELIC SAILING SHIP AS FLUNKY OR SUPERCARGO, AND JOINED A ROCK & ROLL BAND TO MAKE A MILLION LAUGHS...WELCOME ABOARD!!!! PHIL"

Well it sounded like there was a party of magnificent proportion happening and I didn't want to miss out, so in mid-April 1966, I left Hawaii for San Francisco. By that time The Grateful Dead were in full swing. My first Dead show was at the UC Berkeley gym sometime around the end of April.

And The Grateful Dead were on a roll. Back in early 1965, they were still known as "The Warlocks." Phil Lesh was already part of the scene, and through him, I became aware of how they were transforming music into something entirely new. By the end of that year, in December 1965, they had had their first gig under the name “Grateful Dead” at one of Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests in San Jose. I wasn’t there (still in Hawaii), but by all accounts, it wasn’t just a concert; it was an experience, an explosion of music, LSD, and the kind of mind-expanding possibilities of firsts.

By early 1966, things had really started to take off for the band, and by 1967, they were touring nationally.

Between 1966 and 1967, I took up residence in a house on Schrader Street just off Haight Street. My cousin lived there too, and he was selling Oracles and Berkeley Barbs out on the street. There were hundreds of kids coming into San Francisco from all over the country. He’d meet these kids who had just arrived and bring them home. We’d always have people baking bread, cooking rice—just feeding folks until they could find a place to stay.

There was so much of that going on, and I haven’t seen anything like it since.

The Conception of Anthem

In the winter of 1967, while the Grateful Dead were deep in recording Anthem of the Sun, my friend Hank Harrison had come back from South America, following the trail of the legendary beat writer and psychonaut William Burroughs. He brought back with him some yagé (also known as ayahuasca), a powerful entheogenic brew from the rainforest with deep shamanistic traditions. TC and I had been through a lot together, exploring new frontiers of sound and experience, and despite his later abstinence from LSD when he toured with the Dead, he and I decided to close out the year with something bigger.

We headed out to the Valley of Fire, we took the yagé and, just to make sure we "got off" fully, some acid (250µg). The experience was beyond anything I had ever gone through. Although I didn’t know it at the time, Anthem started to take form in my mind—right there in the desert, under the influence of those powerful medicines.

Valley of Fire - PickPik

The combination was visceral beyond words — seeing and feeling things, not in any ordinary sense and a complete ego-death. Eventually, five or six hours later, I remember being aware of my body, like feeling my circulation, and thinking, "Oh, it’s time to take another breath." Breathe.

A few days after, I was back in San Francisco and at Phil’s house. He asked me if I’d do the cover for Anthem of The Sun. I went home, and I thought I’d better get something to work on. The Schrader house had these oil-cloth window shades, thirty-six inches wide, so I took that off. My brother in San Jose helped me cut a circle out of a half inch sheet of plywood, and then I stapled this window shade onto it, and that’s what I drew it out on.

I took the sketch on the canvas to the Dead while they were rehearsing at one of those old theaters in San Francisco. Eventually everyone said, “Yeah!” so I went back and got some acrylic paints and got to work.

Every stroke was tracing something that already existed, just waiting to be brought into the physical world. The lines were projected from my mind onto the canvas, as I drew and painted, using both left and right hands for each respective side, sitting on the floor, as I had no furniture, no easel. For this, I didn’t need any studies or references: it simply flowed. I spent eight to ten hours a day in my room, coming out to eat and for a walk.

Amidst of this, I had no money, nobody really had money. So I’d walk down Haight from one end and ask anyone I saw who had food for a bite. Then, I’d walk down the other side of the street and do the same. Sometimes I’d get a meal out of it. We’d call it begging now. Then, it was … I don’t know. It was a different time.

I worked on it a couple of months through March, then the house next door caught on fire, so a friend, Richard Kane, who I bumped into in Golden Gate Park, said “grab your stuff and come to my place,” so I had a blanket and the paint and the painting and wrapped it in the blanket and then went over to his place in North Beach and for about another month, finishing everything except the background.

The Cover Art

After I flew the unfinished painting to Warner Brothers in Los Angeles to be photographed for the album cover, I brought it back to San Francisco. Shortly after, Richard Kane asked me, “Did they pay you for the painting?” When I told him no, he got a lawyer friend involved, who made a call on my behalf. That worked eventually — Warner Brothers cut me a check for $1,200. To show my gratitude for Richard’s help and hospitality, I gave him the painting and told him, “I’ll finish it someday.” At that point in my life, I had no need for possessions.

Getting on at Life

After Anthem of the Sun, I was done. I went back to Hawaii. That’s where I wanted to be, and I ended up spending almost half my life there, at different times—probably about 25 years in one stretch. I was raising my family there. I’d come back to the mainland for New Year’s Eve shows, but otherwise, I stayed in Hawaii. It seemed like the right place to be. A lot of my friends from the Dead and other bands came to Hawaii for vacations, so it felt like I was on a permanent vacation!

Well, there were a few years when I decided to go back to school - I never had completed my degree, and I did have benefits remaining from the GI bill. At that point, I was deeply interested in botany and mycology. I suppose all those psychoactive plants gave me a new thread to pull on. In this domain, again, it was all about looking at extremely fine details - which was certainly where my head was at.

Finishing the Painting

In 1985, Richard passed away, and his widow, Janice, found herself in a difficult financial spot. I wanted to help and had a little money, so I gave her $10,000. Janice insisted on giving me something in return and we agreed on Anthem. It had been hanging in their bedroom in Healdsburg for years, and by that time, the sunlight had faded the colors a bit.

I hadn’t painted since my days in San Francisco, but I knew I needed to finish what I had started. In 1989, I began by reworking the background and bringing the painting back to life. Then, in two more six-month sessions spread over the following years, I freshened up the faded areas, restoring the colors and lost details.

With the finished painting emerging on my easel, I knew it needed a frame that could match the energy and depth of the painting.

I was living near these experimental stations where, back during John F. Kennedy’s presidency, they had planted all kinds of trees. But when Reagan came into office, they bulldozed the trees for cattle grazing. What they left behind was a goldmine—piles of exotic woods, just sitting there. A friend of mine had a saw and helped me turn the wood into lumber, which I stacked and let dry for about a year.

Once the wood was ready, I started working on the frame with my friend Steve. The process took about 360 hours, piece by piece. I used a variety of exotic woods — mango wood, two types of koa, Purpleheart, Silver Oak, and a kind of eucalyptus. I glued the pieces onto a half-inch piece of plywood, and as I worked, the frame began to take on a life of its own. I carved skulls and flowers into it, symbols that connected with the themes of life and death, creation and transformation which are central to The Grateful Dead, and my own consciousness.

Each part of the frame had its own purpose. The outer part is made of koa, a strong and beautiful wood. The flames, which burst out from the frame, are carved from mango wood, with coconut trim, while the background is made from a type of eucalyptus. These materials weren’t just chosen for their beauty—they were a way to bring the painting’s energy into the physical world, to create something that felt as alive as the artwork itself.

The frame became a work of art in its own right, something that ties the whole piece together. It wasn’t just a border; it was an extension of the painting, a way to ground Anthem in something tangible while also amplifying its themes.

The final piece: Anthem of the Sun, William Walker, copyright 1997.

Anthem of the Sun, on exhibit at San Francisco’s Museum of Performance and Design for me – a Summer of Love retrospective,

Under a Rock

Throughout my life, my focus has always been on my own artistic journey, shaped by personal experiences and deep collaborations with musicians, rather than chasing commercial art success. While I did create a few posters for San Francisco bands, including Mobius—a group of friends from my Las Vegas days—my main artistic connection was always with Phil Lesh and the music of the Grateful Dead.

I admired the work of poster artists like Stanley Mouse and Rick Griffin, but I never sought to join their ranks or follow the same career path. While I was in the Marine Corps, I made a friend, Jerry, who was contemplating a future in architecture or dentistry. He talked to Frank Loyd Wright's brother about it, and ultimately his advice was, as an artist, you have to pick between doing something that interests you or money. That stuck with me. Jerry became a dentist, and, me, I made art, but not for money. My art was personal, rooted in my experiences with philosophy, psychedelics, and the profound connection I felt to the music that surrounded me. Commercial success wasn't interesting. It was about expressing the visions that came from within, whether they were inspired by a psychedelic journey in the desert or the energy of a live Grateful Dead show.

That said, after finishing the painting, I didn’t make it a priority to make a business of it. A friend got it into a San Francisco Museum of Performance + Design exhibition, Somethin's Happening Here! Bay Area Rock 'n Roll 1963-1973. That was neat. All of my friends and family loved the painting and so I made some prints of it.

– although a friend got it into an exhibition in San Francisco’s Museum of Performance and Design for me – a summer of love retrospective, and that was neat. But I’m not, around 2007 I moved to the desert – Pele chased me off the Big Island with her constant eruptions and air pollution. I was again high and dry – the best place for Anthem and its meticulous frame was not the desert, so I crated it after getting it back from the exhibition and my friend, and it sat in my sister-in-law’s garage for many years.

And, so, Anthem stayed in a box…UNTILL NOW.

In 2024, fifty-six years after the project started, we are finally getting the finished Anthem out of the box, and into the light, with many thanks to Brian Chambers of The Chambers Project.

The End

I hope you enjoyed this story. It’s been a long strange trip.

In the end (or really, just another beginning?), Anthem is a visual representation of my journey—through the cosmos, mathematics, the depths of my own consciousness and my body. It’s not just a painting; I see it as the terrain I’ve explored, from the vastness of the universe to the microcosmic depths of the mind and body. It’s a testament to the interconnectedness of all things, the cycles of creation and destruction, and the challenges we must face to transcend ourselves. Every symbol, every color in Anthem is infused with the experiences that shaped me—from the stars above Arizona to the serpents in the Valley of Fire, and the glorious musical soundtrack of The Dead that accompanied the birth of this consciousness.

My hope is that anyone who looks at Anthem can feel that journey too, and perhaps embark on one of their own.

I was drawn to patterns, and in particular of the "Thousand Petal Lotus" from yogic physiology, a profound metaphor and mathematical construct. My mathematical explorations revealed that this lotus, expanding outward in successive rings, could encompass not only our observable universe but potentially countless others. I was intrigued by how this idea could expand beyond the confines of our known universe, using concepts like the Gravitational Quanta as the building blocks. While I couldn’t include the lotus in the album cover before print due to time constraints, I later incorporated it as the "Source" in the finished version of Anthem, symbolizing the origin of everything—the universe, consciousness, and all the connections in between.

Thank you, Traveler. Be kind. Much Love,

-Bill

Visit Anthem in Grass Valley California.

Visit The Chambers Project for more information.